Illuminations: Stories. Alan Moore. Bloomsbury Publishing.

By Apuleius Charlton

Special guest blogger

I can remember reading “A Hypothetical Lizard” the first time in my dorm room, lit only by the light of the screen as evening fell. I had found it somewhere online, perhaps from the Alan Moore Yahoo! group I was a member of at the time, perhaps a friend had found it and sent it to me. I wasn’t unused to reading prose from Moore, having recently finished Voice of the Fire, but at the time I was still much more used to his comics work and reading interviews where he complained (rightly) about the Watchmen film and every once in a while released a new tidbit about the forthcoming League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Century. There was something about his writing, even though this story was from a year before I was born, that was strikingly consistent: Alan Moore always speaks with his voice, no matter how it reaches you. Moore dwells often on the same themes, even if those themes are viewed from a prismatic perspective- what I found was at once familiar and unsettling.

“Familiar and unsettling” would be a fair way to describe my reaction to many of the stories in his recent collection, Illuminations.

In “A Hypothetical Lizard” I found a small cosmos in the House Without Clocks that was exotic and erotic, a bit tempting and wholly tragic. But more to the point, we must congratulate Moore in hindsight for the trap he laid and cinched in the story; by providing us with a narrator who was trapped, Moore highlights the inert role of reader as we watch the inevitable unfold in his vignette of a beautiful hell. The complexities of Rawra Chin and Foral Yatt’s past is boiled down into lamb’s blood by an unnecessary reunion and a foolish reentwining- if nothing else, the story is an excellent argument to leave past relationships alone. The symmetry of revenge and ill-gotten inspiration is perfect. After reading the story for the third or fourth time when I purchased Illuminations, the suction of its resolution is surprising. There’s aching all over in the story; the yearning to understand, to enjoy and be enjoyed, to be recognized becomes something like a wildlife documentary. We root for the gazelle while understanding that the kill is the point of the scene, the thrill of it all; and that after all, a lion has to eat. But while the story is precise, it doesn’t strike one as particularly just. It just Is. And perhaps Som Som, our neurologically diverted porthole into this drama, has the best reactions when she utters some non sequitur about her own half-remembered life.

After reading “A Hypothetical Lizard,” I looked up other stories set in Liavek, the shared world that Moore’s story takes place in, and was sad about how the couple I read (by other authors) didn’t live up. There is no reason for such disappointment to take place with Illuminations; as some stories appealed more to me than others, they are all brewed using the excellent mash that is Moore’s mind.

The second and third stories in the collection were my favorites. Although both had been planned for earlier publication, and one actually had been published, this was my first time hearing about either. Alas, the loss of that Alan Moore Yahoo! group seems to have kept me out of the loop. For myself, “Not Even Legend” was the highlight of Illuminations, combining an emphasis on perspective and the possible nature of the supernatural that left me close to tears at certain points. (I am going to endeavor at this point not to give much away about the stories because; firstly, that would be an exhaustive and overly long review and secondly, Moore’s work speaks for itself quite clearly without my extrapolation.) “Not Even Legend,” written during the height of the quarantine efforts during the Pandemic, seems to suggest that perhaps more baffling than aliens, ghosts or entities we might as-of-yet be wholly unaware of, is ourselves to each other. The story, full of misapprehension and mistakes and ends, keeps Moore’s inevitability strongly in play from the beginning. Also, Moore’s proposed categories of “unknown unknowables” are deliciously imaginative. The second story, “Location, Location, Location” is either more or less straightforward than “Not Even Legend” (I can’t decide at this point) and just as hyper-disturbing/fascinating. Some of the themes and imagery will be familiar with anyone who reads Moore regularly—apocalypse, our teetering institutions and sarcastic literalism—but there’s something to say about reading an author obsessed with apocalypse writing about it as they and the world around them grow older. At the very least, “Location, Location, Location” helps Moore’s reputation as the foremost expert, living or dead, on English religious-eccentrics.

Having been a subscriber of Moore’s lamented/celebrated Dodgem Logic, I had already read “Cold Reading '' many years ago on a December evening, when it should be read. I liked this story and remembered it pretty clearly; it follows in the great British ghost story tradition of M. R. James and Robert Aickman, but with some updates for those of us familiar with the skeptic-believer debate. It does lose something without being presented alongside a short comic about Lady Gaga serving cocaine and dildos to children on Christmas instead of bangers and mash. “The Improbably Complex High-Energy State '' is a story about Boltzmann brains and concerns Moore’s other favorite topic aside from apocalypse, creation. This story premiered in a new issue of New Worlds, which I was saddened to find out I had missed, but I feel the authors at Moorcock’s run of the magazine would have approved of it. And before we arrive at the big number of the performance review, we find the titular story “Illuminations.” Evidently, this was inspired by a disastrous seaside trip Alan Moore embarked on fifteen years ago, yet less time has passed since the story's inception and now than that inception and the holiday(s) that inspired Moore. “Illuminations,” if I understand, is a condemnation of nostalgia and seeking to recapture times gone by; perhaps memories, like relationships, are best left undisturbed.

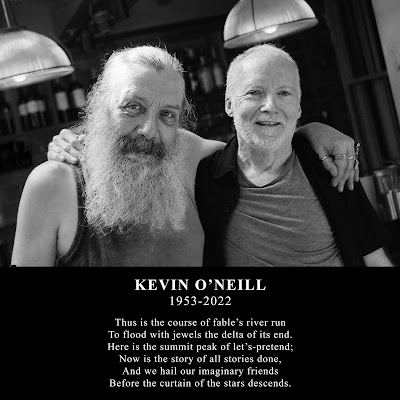

At this point in the review, now we come to “What We Can Know About Thunderman,” the headline affair of the book, even if it didn’t make the title page. Like “Illuminations,” “Thunderman” is a recrimination against nostalgia, but instead of focusing on a disappointing vacation, it considers the industry and cultural phenomenon that is comics books. It is a fairly easy to decode roman a clef for the American comics industry, although I would have to be a bigger comics buff to recognize who everybody relates to in our “real” world. The main thrust of the plot concerns some editors and writers at American comics (a stand in for DC) in the mid-twenty-teens and aligns nicely with the societal breakdown that began its first seismic thrusts that are still shaking away at our foundations today. Here is Moore at his wittiest and most jaundiced; poignantly, it is dedicated to the recently departed Kevin O’Neill, another genius who was unfairly dealt with in an industry that while meant to build on the imagination, instead often devolved into crass commercialism. This is, I feel, in some ways a culmination of those many interviews I read with Moore castigating DC and Marvel back in the aughts. I felt primed, after a manner, by the biographical snippets at the beginning of each of the last six issues of The League (“Cheated Champions of Your Childhood!”), where O’Neill and Moore covered the tragic careers of British comic creators. Don’t act surprised, reader, in what you find herein. And now I must say, people, come for the invectives and anger; stay for the astounding display of Moore’s virtuoso writing skills.

After Jerusalem, I didn’t think I was ever going to be as surprised and enthralled by Moore’s word-weaving, but he somehow pulled the trick off again. He surprises the reader with tales-within-tales replete with descriptions that are thought-provoking and hilarious. My favorite scene in the arabesque that is “Thunderman” would have to be two men looking through their former editor-in-chief’s New York apartment- the sheer joy of seeing how many variations Moore could devise for “pornographic magazine” was thrilling. I kept expecting for him to run out of new ways to describe the same thing and he simply doesn’t. I felt breathless by the end of that scene and in many ways, it was from laughter. That’s one thing I’ve always felt like critics miss about Moore; even when he is taking a piss, he is truly, deeply, funny. Moore has done a couple of impromptu stand up routines in the past and I think he would have made an astounding comic; if only we could slip into that alternative dimension and read what he would have to say about that industry.

The sticking point with “Thunderman” is that Moore is not only attacking the comics industry, but fandom and the medium itself. It is no secret that Moore, who I would argue is as great and important as Jack Kirby is to the medium, views comics with utter disdain. Out of his massive corpus of comics, he only acknowledges five of them in his “By The Same Author” page at the beginning of the book. Moore’s grievances are understandable, but some readers will feel attacked or feel as if something they love and consider important is being unfairly maligned. While I have very little loyalty to comics (to the point that I used to describe myself as “an Alan Moore fan, not a comics fan,”) I can see where this will strike some as pure bitterness. Indeed, it is nigh-amusing to think of someone who loves Watchmen or V for Vendetta, without having read or listened to Moore’s interviews, eagerly picking this up. It isn’t pretty. This possible roman a clef veers a little too close to hell. In the same reality-defying prose he used in Jerusalem, Moore serves us the teased pappardelle of our real selves spooned out with the bolognese of our bloody immaturity, seemingly forevermore. Don’t expect comfort here; here there be tigers.

Rounding out the collection we have “American Light: An Appreciation” and “And, at the Last, Just to Be Done with Silence.” “American Light” was another favorite of mine, based on Melinda Gebbie’s recollections of San Francisco and the Beat scene which went much further than Ginsberg, Kerouac and Burroughs. This is a work akin to “The Crazy Wide Forever” from the much earlier The Black Dossier insomuch as we are seeing Moore’s expert imitation of Beat writing; it is also a much more mature piece of writing than what was called for in that delirious compendium. As I began the story/poem, I almost thought that it was just a device for Moore to write a complex poem and provide annotations so that the reader could understand just how great his poetic skills were. Then the story quickly formed in the tension between the poem and the footnotes; like the Beat scene, like America in the twentieth century, it is a story of selfishness, genius and those left in the wake. I highly recommend it.

As I am so shamefully ignorant that I haven’t yet identified what event “And, at the Last, Just to Be Done with Silence” is about, I feel I have little qualification to write about it. But this is one of Alan Moore’s meditations on death and memory and is a fitting end piece to the collection. Like “American Light,” it did recall an early work of Moore’s, namely the chapter from Voice of the Fire:” “Confessions of a Mask.” Moore ends his work in silence.

Yet, joyfully, we are assured that Alan Moore is still rich with ideas and projects for future works: his Long London sequence is still forthcoming and boy, I can’t wait to read what all it entails. Illuminations is as worthy of attention as anything Moore has previously published, and that is to say quite a lot. Sometimes I feel like a Worsley Porlock to his Joe Gold, but thank Whomever that Moore walks among us and wields his pen. Oh, the book is very sexual and you’ll be left slightly horny as you stare slack jawed into the starry abyss. Fall to!

.jpg)